Too often we overlook the full capabilities of the tools in our paint boxes and forget that they were designed to ease our workload and extend the impact of our work. Let’s talk a bit about brushes.

The artist paint brushes in our hands today are the product of centuries of evolution. They are modern marvels, the result of extensive, in the field, use and contemporary engineering. That’s all wasted, however, if we ignore all they can do.

It’s important to use the proper brush for the job at hand. My favorite workhorse brush, when painting with oils or acrylics, is the bristle brush. This baby’s stiffness can move the thickest of paints across a canvas and is great for scumbling, dry brush and impasto techniques. It’s my go to brush for most of my painting needs.

When you’re painting wet into wet, especially in a single session, alla prima, you’ll find the bristle brush less effective in paint over paint application. It’s rigidity tends to pick up the wet paint from lower layers, mixing them with the new paint you’re attempting to apply, preventing you from applying clean new strokes. This is when you want to utilize your sable brushes. A light touch with one of these, will float the new color on top of the previous applied wet layers.

Glazing (transparent layers of color utilizing large amounts of painting mediums) can be accomplished by either bristle or sable brushes. It all depends on the viscosity of your mixture.

I covered the proper brush for the job in more detail in a previous post, “Be Good to Your Brushes & They’ll Be Good to You!”

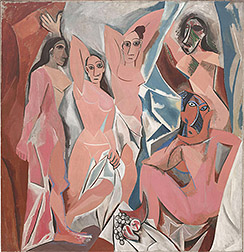

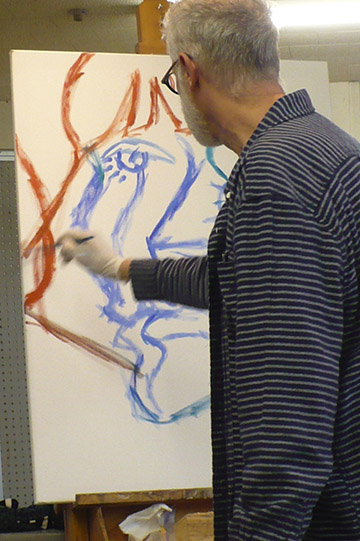

What I actually wanted to talk about in this post was allowing your brushes to do some of the work for you. All the subjects you paint possess visible characteristics quite different from each other. These characteristic are the result of things like growth patterns, chemical make-up, environment wear, etc. The leaves on a tree present a much different surface characteristic than, say, the granite face of Half Dome, in Yosemite, for example. Yet, it’s easy to ignore this fact and apply paint to canvas in the same uniform manner, when executing all elements in our compositions. Boring!

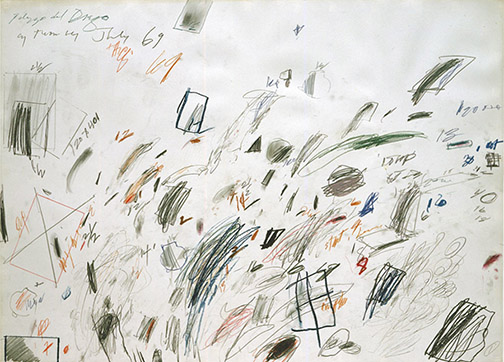

Instead, pay attention to how the elements you’re painting grow, what they’re made of, how they move, how their surface reflects light and color and then allow your brushwork to communicate this. The British painter, Alwyn Crawshaw, famous for tv shows, books and videos on painting, suggests you try to become the element you’re painting, “I’m a fluffy little cloud!” Then paint the element accordingly. A bit over the top form me, but I get what he’s saying.

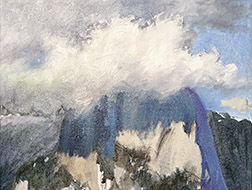

What does this actually mean: allow your brush to reflect the characteristics of various elements in your paintings? Well, when studying the granite face of a monument like Half Dome or El Capitan, in Yosemite, you’ll notice it has very chiseled characteristics with strong vertical concave and convex up and down forms. A great approach in painting these, might be to use the edge of a flat brush to create vertical strokes, occasionally rolling the brush a bit, from side to side, to vary width in the process.

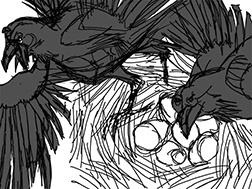

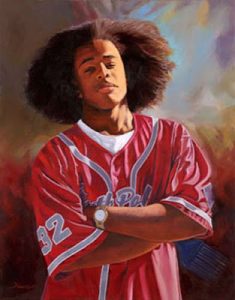

Foliage on trees often starts with a glob of paint and ends with a flick of the brush towards the edges. With clouds, rolling the brush around, then flicking an edge here and there might be the best solution. Ground is often a series of short horizontal strokes, reflecting the years of overlapping footprints of man and animals. The directions of strokes over a face in a portrait reflect the anatomical structure beneath. Strokes representing a flowing river tell of the repeating pattern it creates as it travels around rocks and over an uneven river bottom.

How you portray the various characteristics of the elements that make up your paintings is a personal choice, there’s no ONE good solution. I’m suggesting that your paintings will be more dynamic, more interesting, if you consider the actual structure, make up, of the elements in your compositions, then reflect this to your audience with how you use your brush in your paint application.

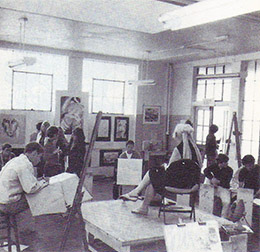

So, get an art school education if you can, but don’t despair if it isn’t in the cards. With proper dedication and exposure, you can get there on your own, the journey is just a significantly longer one.

So, get an art school education if you can, but don’t despair if it isn’t in the cards. With proper dedication and exposure, you can get there on your own, the journey is just a significantly longer one.