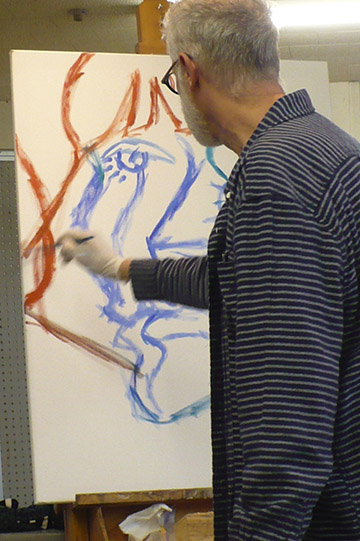

First let me apologize for my complete lack of posting over the last few weeks. I became buried with unsolicited work (always a good thing) and there just weren’t enough hours in the day to slice out time for writing (or painting, for that matter). I’m not kidding about the project volume. I’m currently working on 2 mural painting for 2 separate children’s hospitals, 4 branding projects for 2 new clients, I’ve taken on a new private student, have begun my second term as a teaching artist for the Mariposa County Arts Council and School System, designed an elaborate tattoo for a local businessman and I’m putting the finishing touches on a new website for Sierra Art Trails. Whew! Anyway, enough with the apology and on with the post.

I recently came across a filing folder of my childhood artwork. Unknown to me, my mother was saving much of what I created, as I was growing up and decided last year to pass the collection on to me. My mom and dad both turned 90 this year and my mom’s beginning to distribute these mementos among her five children. I never bothered to look through it, at the time, instead, just shoving it onto a shelf in the closet of my studio.

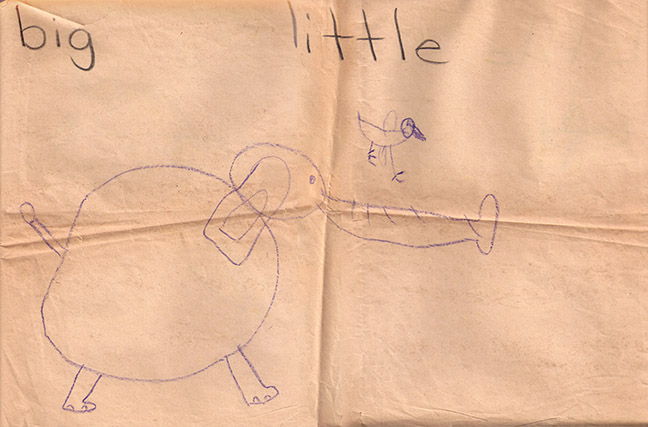

Looking for something else the other day, I noticed the folder and took a look inside. To my great surprise it contained a drawing pivotal in my life. A very early creation I had no idea my mother had procured and preserved. Right on top, quarter folded, was the drawing shown at the top of this post.

This was an early art assignment (maybe my first art assignment), given to a 5 year old me by my kindergarten teacher, Mrs. Macnamara. The class was to draw something big and something small (as our teacher had written across the top of our blank sheets of manila paper, with a thick black crayon). I apparently decided to make animals my focus.

I’m sure I’d been to, what was then known as, the Griffith Park Zoo many times by then and experienced the elephants there, first hand: sizable beasts, when compared to a 5 year old looking up at them. So, when I thought of really big animals, elephants were an obvious choice.

I spent a lot of my 5 year old life playing outdoors with other kids in the neighborhood. In fact, I began kindergarten with my left arm in a cast to hold the broken bones still while they re-knit, an injury sustained through a bad fall, rough-housing with some of the older kids on the block. Anyway, I saw a lot of birds outside. So, under small I drew a bird. Seemed right to me!

When my teacher collected our drawings and reviewed them, she asked me if she could mat my drawing and put it up on the wall for the upcoming Open House. A little light went on in my head. Hmm, why me?

I got an answer to my question a few days later, when during the Open House, Mrs. Macnamara encouraged my parents and I over to the wall where my drawing was being displayed. She explained to my mom and dad why she selected my drawing to display. In addition to her liking the quality of this early effort (all smiles) I was the only student in the class to use comparative analysis in arriving at my solution. While everyone else in the class had drawn big and small version of the same object: a big sun and a small sun, a big house and a small house, etc., I chose to draw an item that was actually big in the real world with one that was truly small.

I felt myself swell with pride at the attention brought to this effort, early in my academic career and at that moment, then and there, decided what I wanted to do with the rest of my life!

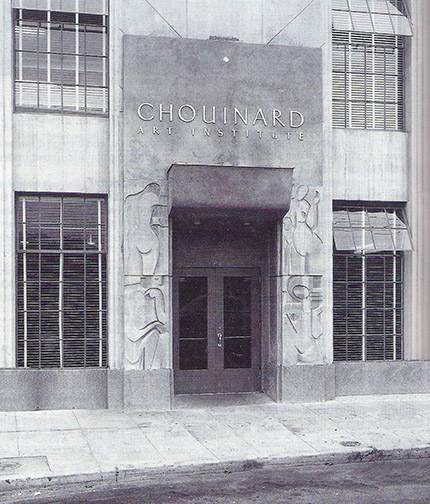

So, get an art school education if you can, but don’t despair if it isn’t in the cards. With proper dedication and exposure, you can get there on your own, the journey is just a significantly longer one.

So, get an art school education if you can, but don’t despair if it isn’t in the cards. With proper dedication and exposure, you can get there on your own, the journey is just a significantly longer one.

Another central topic surrounding our competition judging discussion was the importance of who the selected judges are: their background and expertise. Organizations have a lot of tasks on their plate when putting together an exhibit or competition and too often judge selection it made quickly, without adequate consideration, in an effort to mark the task done and move on to one of the other items on the list. The problem is compounded if you’re making the selection for an organization who offers competitions annually or even more frequently. In attempts to avoid using the same qualified judges too often, it’s easy to relax standards a bit, in the name of adding variety to the judging panel. Don’t do it! Who is selected to judge the competition is the single most import decision made in an art competition. Unqualified judges make for unfair, competitor head-scratching decisions.

Another central topic surrounding our competition judging discussion was the importance of who the selected judges are: their background and expertise. Organizations have a lot of tasks on their plate when putting together an exhibit or competition and too often judge selection it made quickly, without adequate consideration, in an effort to mark the task done and move on to one of the other items on the list. The problem is compounded if you’re making the selection for an organization who offers competitions annually or even more frequently. In attempts to avoid using the same qualified judges too often, it’s easy to relax standards a bit, in the name of adding variety to the judging panel. Don’t do it! Who is selected to judge the competition is the single most import decision made in an art competition. Unqualified judges make for unfair, competitor head-scratching decisions.