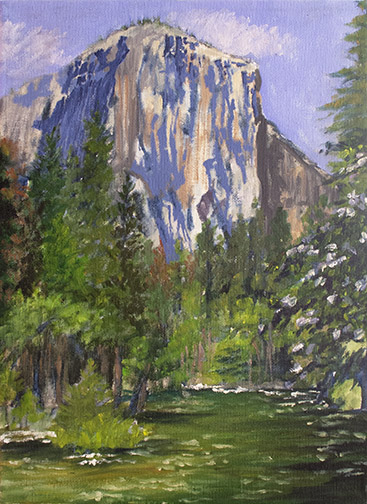

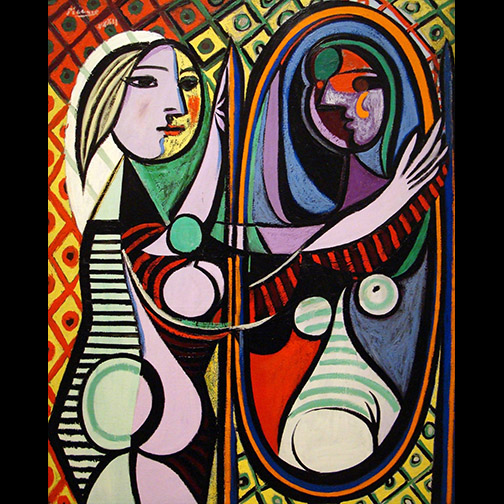

I work both abstractly and representationally, so my work connects me with representational painters and enthusiasts, as well as those who work with or love abstraction. Because I use multiple viewpoint perspective* in my abstract work , it often initiates conversations about cubism and Picasso. Contributing to these discussions, I’ve discovered a whole lot of people who tell me they don’t like Picasso…in fact, some say they HATE Picasso!

Further inquisition reveals that most of this group misunderstand what they’re perceiving when they stand before a Picasso work. You’ll often overhear a judgement like, “That’s not art!,” from someone viewing one of this Spaniard’s paintings or sculptures. In a way, they’re right, it’s NOT a particular KIND of art. The reality is that since the middle or late 19th century Art has been divided into categories.

Prior to the mid 19th century all Art fell into one category, representational art. Art had actually been more of a commercial endeavor and was often the product of a team of craftsmen, working under the direction of a master craftsman to arrive at a product commissioned by a paying customer. Most of those commissions were initiated by the Catholic or Orthodox Churches, which both required an almost impossible number of images, sculptures, stained glass windows, alters and even churches to communicate their message to an illiterate public. These collections of craftsmen were often capable of designing and fabricated all the above listed items for their customers, a kind of one stop shop. Representational imagery was key to communication, so the competition among the Art Shops was fierce as to who could delivery the most convincing Realism.

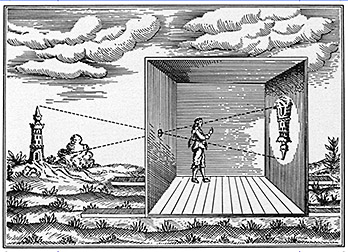

The artisans had no qualms or guilts surrounding mechanical assistance in arriving at their representational ends. They were competing with each other in a race to create the most realistic images possible. Realism translated into bucks, more commissions meant more money in their pockets, so when the single or vanishing point perspective system, for achieving realistic perspective, was uncovered, they lapped it up. The camera obscura, a mechanical device that allowed projection of the world onto a piece of paper, panel or canvas for tracing, introduced during the Italian Renaissance, was welcomed by many of these craftsman, as a quick and accurate method for achieving realism. The point is, Art was a highly commercial endeavor, the faster, more accurate and efficient images could be created, the better. No one cared how they got there. There was no such thing as a Fine Art, only paying customers.

In the 16th Century Protestantism arrived and brought with it The Reformation, which sought to return believers to religious fundamentals and strip away, what was felt, were blasphemous religious practices, among them, the creation of graven images or idolatry. Remember the printing press had been invented by now and people were beginning to read, the church was no longer dependent on imagery for communication.

With the loss of this meal ticket, the popularity of the multi-artist studio began to give way to solo artist practitioners. They may have utilized an assistant or two, but the production process was greatly scaled down. Efficiency and the assistance of whatever devices were available was as important as ever. The major customers now, were civic institutions or wealthy patrons interested in having pertinent events, important individuals or history (real or fictional) recorded for posterity. Again, communication was the goal and realism the best vehicle for the communication.

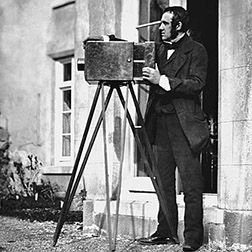

Remember the artist’s friend the camera obscura? Well, over time it was fitted with a ground lens and reduced in size, from its original configuration as a small room, to something that could be carried around and used on location. In the middle of the 19th a practical method appeared that could take the image captured directly by the camera and reproduce multiple copies of it. Photography was born. With real images of people and events now available, painted versions, as documentation, were less necessary or desirable.

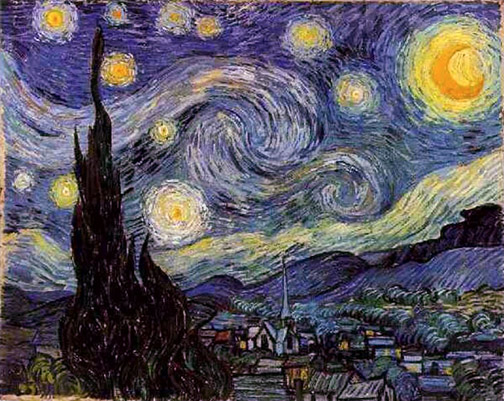

This unexpected development (excuse the pun), changed the way artists perceived what it was they were doing. They became more introspective, started looking at how they applied paint, how they mixed color, how they delivered the illusion of space, etc. One outcome was Impressionism, where, less concerned with realism, artists applied paint loosely and dabbed raw color directly on the canvas, requiring viewers to complete the paintings, in their mind’s eye. Here, for the first time, a division in art begins. Art is divided into art for commercial purposes (illustration) and a new Fine Art, an art for art’s sake.

Galleries for public viewing of art began to appear in the middle 18th century, where, prior to this, all would have been secreted away in private collections of the church, royalty or the wealthy. These public spaces really took off in the 19th century, where the average citizen now had access to viewing art in every city, around the world.

With the stage now set for Picasso’s entrance, I’ll present the man himself in my next post and explain why he is considered the creative genius of the 19th and 20th centuries.

*An approach that considers the subject matter from all sides, then represents that data, at the same time, in a single image…think cubism.

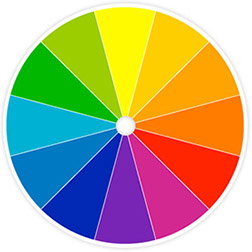

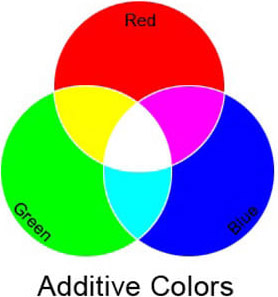

Additive color theory is important to understand, though, since it is all about how the LIGHT color spectum functions, unless you’re a photographer or lighting director in theater or film you won’t have the opportunity to manipulate it. It is the system by which you view color in the world. The primary colors in the Additive color system are red, blue and green (not red, blue and yellow, the primaries in the Subtractive color system). Mixing all 3 primaries results in white light. When you see an object as red, like an apple, the molecular make up of the apple is such that it is absorbing all colors in the light spectrum, but red. Because the apple can’t absorb the red light, the red light rays bounce off the surface of the apple and back to your eye. Ironically, you could say the apple is every color but red, since it’s absorbing all the other colors in the light spectrum, but red.

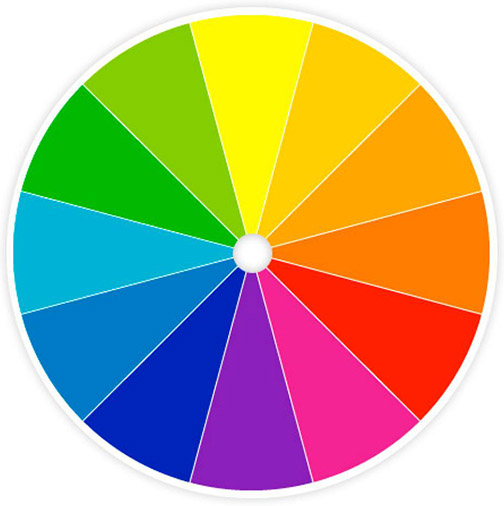

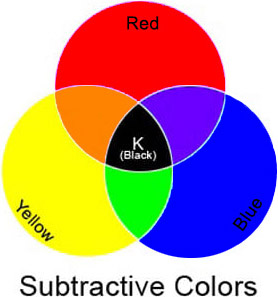

Additive color theory is important to understand, though, since it is all about how the LIGHT color spectum functions, unless you’re a photographer or lighting director in theater or film you won’t have the opportunity to manipulate it. It is the system by which you view color in the world. The primary colors in the Additive color system are red, blue and green (not red, blue and yellow, the primaries in the Subtractive color system). Mixing all 3 primaries results in white light. When you see an object as red, like an apple, the molecular make up of the apple is such that it is absorbing all colors in the light spectrum, but red. Because the apple can’t absorb the red light, the red light rays bounce off the surface of the apple and back to your eye. Ironically, you could say the apple is every color but red, since it’s absorbing all the other colors in the light spectrum, but red. In subtractive color theory the primary colors are the more familiar red, blue and yellow. This is the system we work in, when we mix paints. The combination of all three primaries in this system result in black. You’re mixing pigments in this system, not light. Your eye perceives the colors you mix, however, in the same way it perceives the colors of the light spectrum. The molecular structure of any particular pigment color absorbs all color but the color you perceive. Blue, for example, absorbs all colors of the spectrum accept blue light and, therefore, bounces or reflects the blue light back to your eye.

In subtractive color theory the primary colors are the more familiar red, blue and yellow. This is the system we work in, when we mix paints. The combination of all three primaries in this system result in black. You’re mixing pigments in this system, not light. Your eye perceives the colors you mix, however, in the same way it perceives the colors of the light spectrum. The molecular structure of any particular pigment color absorbs all color but the color you perceive. Blue, for example, absorbs all colors of the spectrum accept blue light and, therefore, bounces or reflects the blue light back to your eye.