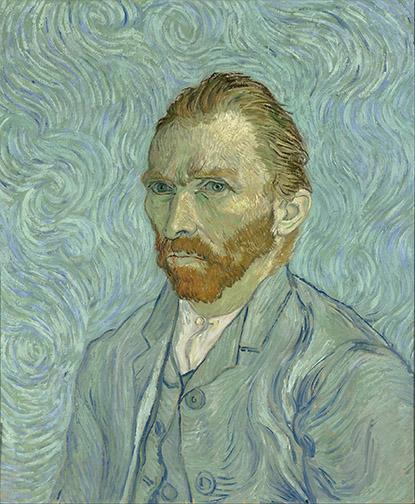

Vincent van Gogh’s work spoke to me at a young age (6 or 7) and I’ve continued the conversation with this very special Dutch artist my entire life. I first discovered his work in a Child Craft encyclopedia, one of the volumes in the full set my parents had purchased to support the new family they’d begun. It was the first of many books in which I’d learn about his tortured life and magnificent product over the years. With each tome new pieces were added to the complicated picture puzzle of his life.

Vincent never showed any special affinity, interest or talent as an artist before he decided he wanted to be one at age 28. 9 years later, at age 37, he was dead. Over just 9 years he’d taught himself, first to draw (2 years), then to paint, producing 2,100 works of art and establishing himself as one of the most influential artists in Western Art. Not so much a little known fact as a phenomenon often overlooked.

While it appeared the older Vincent was taking great advantage of his younger brother Theo, in actuality it was a business arrangement. While Theo was supplying the funds that enabled Vincent to paint, all the paintings belonged to Theo and Vincent shipped them off to his brother, as soon as they were dry enough to travel.

Vincent was a kind, compassionate individual, in the extreme. In his earlier attempted vocation, as a missionary in Belgium, he ruined his own health, first giving away all his food and most of his clothing to the poor miners there and then sleeping on a bed of straw on the floor, after he’d torn all his bedding into bandages for the treatment of those injured in the mines. Uncomfortably with his sacrifices, the church asked his family to bring him home.

Later, when he was painting in Arles and would pick up funds wired to him from Theo, he’d often arrive home from the post with just pennies in his pockets, having given the bulk of his newly received funds to the poor and homeless he met on the street.

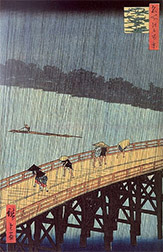

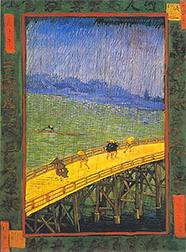

Van Gogh was heavily influenced by Japan’s reopening of trade with the West after 200 years of isolationism. There was such an insurgence of Japanese objects in Europe, that Japanese prints were found, wrapped around ceramic objects, used as packing. Van Gogh’s work began to include outlines, an element missing from Western painting for centuries, but a primary element in Japanese prints. His areas of color were greatly flattened. And something I’d never noticed, prior to recently reading a van Gogh biography translated from Dutch, Vincent eliminated shadows from his paintings. Shadows do not exist in Japanese prints.

Even his migration to the south of France, his attempt to begin an artist’s colony there, was, in his words in a letter to his brother Theo, the seeds of a “new Japan,” as he understood it. His “Bedroom at Arles” a depiction of his new monastic Japanese dwelling place.

Contrary to common belief, Vincent’s work was gaining notoriety during his lifetime and he was offered multiple shows in Paris. Unfortunately, he inflicted a great dilemma upon himself. On one hand he was desperate for financial success, to remove himself as financial burden from Theo, but afraid that the same success would ruin him as a painter. Afraid that popular paintings would dissuade him from experimentation and encourage him to repaint the same paintings over and over again.

Tough case!