Many factors came together, at a particular place in time, for Impressionism, one, to come about and two, to succeed.

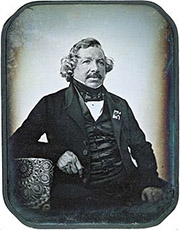

First was the arrival of a fairly efficient method of making tangible, hold in you hands, copies of the images captured by a camera. Cameras, in the form of the Camera Obscura, had been in use by artists since before the Italian Renaissance, but a practical means of recording the images viewed through a box with a lens didn’t come about until about 1840. It’s also significant that this development (excuse the pun) was revealed by Louis Daguerre, in Paris.

Photography quickly replaced the artists as visual documenter and encouraged them to look introspectively at what it was they did. Turner, Delacroix and Manet were some of the first to move away from treating their paintings as if they were a window through which to view subject matter, paying more attention to the canvas surface and its 2 dimensional attributes. They flattened their picture planes and explored the expressive qualities in paint application.

Driven by the needs of its growing textile industry, The Industrial Revolution introduced new, brightly-colored pigments to the artist’s palette: cadmium yellows, reds, oranges and greens, cobalt based colors like blue and violet. Prior to this, only earth toned colors were available. The most brilliant paint color in the Renaissance palette was something like an Indian Red.

American John Rand enabled artist color portability with the invention of the tin paint tube, in 1841. Before his invention, the most popular container for storage of mixed colors was a ram’s bladder. A bit of discouragement in transportation of paints.

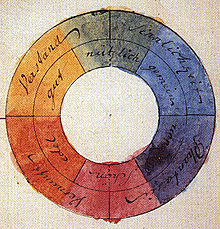

The french easel appearing in the mid-19th Century, also encouraging outdoor, on location work, but one of the biggest developments changing the direction of painting was artists exposure to 19th Century scientific discussions of Color Theory. Although color theory principals actually appeared in the notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci, the study was furthered by Isaac Newton in the 18th Century, then fine tuned and published widely throughout the 19th Century, accelerated largely by the color needs of Industrial Revolution’s textile industry. Primary, secondary, complimentary and tertiary color and how it is produced in nature was being discussed openly for the first time, along with the publication of Color Wheels and charts, leading directly to the Impressionist use of Broken Color and Pointillism.

So these developments and innovations brought Impressionism to the canvases of Monet, Renoir, Cassatt, Pissarro, Degas, Morisot and the others, but “If you build it they will come,” does not always work out, the paintings of these iconoclasts were far from well received. In fact, the label Impressionists was derived from an insult by a French art critic, of the period, Louis Leroy, who described an exhibition of the work as merely impressions of paintings. Bad boys and girls that they were, the painters proudly adopted the insult as a label for their movement.

Like the Beatle’s George Martin, there was another individual, behind the Impressionist’s curtain, a French expatriate art dealer, living in London, Paul Derrand-Ruel, crucial to Impressionisms success. Derrand-Ruel believed in their work, when no one else did, and put his money where his belief was, purchasing their canvases in bulk, providing them additional monthly funds, paying their bills for rent, tailors, paint suppliers, doctors, etc., keeping them afloat and painting. He also provided moral support, even offering a room in his home to Monet, for use as a studio. Derrand-Ruel loaned Monet the funds to purchase his now famous home Giverny. The art dealer tried many methods, at the time untraditional, to gain popularity for his artists, print reproductions, solo shows, but it was a trip to America with 300 paintings that proved the ultimate solution. American buyers carried none of negative prejudice towards the work, present in Europe, and lapped the canvases up.

Ironically, through the efforts of Paul Derrand-Ruel, it was America, not France, responsible for survival of the artists and the success of Impressionism!